Remembering JP

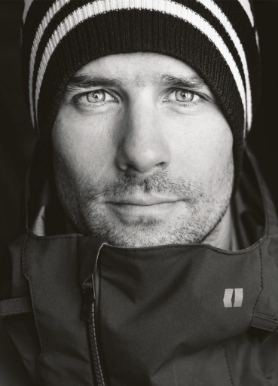

There are a million things that can be said about JP as a skier—how he pioneered and transcended genres, and the indelible mark he has made on the sport. But there is so much more: he was a genuinely good human; he was my favorite person to be around because he was hilarious and because he was kind.

There are a million things that can be said about JP as a skier—how he pioneered and transcended genres, and the indelible mark he has made on the sport. But there is so much more: he was a genuinely good human; he was my favorite person to be around because he was hilarious and because he was kind.

In the summer of 1997 I watched a VHS tape of JP Auclair and JF Cusson skiing the park at Mt. Hood. It was a time when snowboarding was peaking and, in many places, skiers weren’t even allowed in the park. Skiers certainly weren’t doing tricks that rivaled snowboarders—in difficulty or in style. To see JP and JF doing cork 720s blew my mind, and, as a snow sports photographer, I wanted to meet them. At the time, I was a senior photographer at Snowboarder Magazine and I had begun contributing with a start-up ski magazine called Freeze. The following spring the photo editor of Freeze blew out his knee and in his place, I was sent to the Nordic jib land, Riksgransen, Sweden to meet these guys.

JP and I hit it off and that’s how it began – 16 years of traveling and shooting with him. Often, those travels were the kind which involved appearances, autograph sessions and less than ideal ski situations. He would put on a smile and give it 100 percent at an awkward press conference in China when we knew Interior BC was getting hammered. He would shred the icy slopes of Quebec when duty called, or log long hours in the Armada office to slam out a product video. JP was a champion no matter how adverse or inane. That was part of what made him so good.

Ironically, JP and I had a shared sense that what we were doing, while fulfilling in context, at times seemed frivolous. We spent our lives traveling to the far ends of the earth, and we weren’t doing it to build bridges or irrigations systems or to help people have clean drinking water. Instead, we were doing it for skiing.

We used to talk about how skiing and the snowsports industry didn’t really make a difference in the world. In his downtime, JP started Alpine Initiatives to help orphans of AIDS victims in Meru, Kenya. He went to Kenya for a couple of summers to actually build these structures with his bare hands and minimal tools. Real grunt labor, reinforcing what a better person he was than most, myself included. Alpine Initiatives continues today. Their mission has been refocused to support mountain communities here in North America and is one of the many legacies that JP has left us here on this world.

It is not until now, that he is gone, that I realize that some of the fondest memories of my adult life are from crazy trips (with JP) to Turkey, China, Norway, British Columbia, Alaska, Japan, and New Zealand. But of course I loved him that much. We started a fucking company together. JP and I started Armada to save skiing. That he’s not here to see what happens with it, and with skiing and with his son and with everything is mind-numbing.

JP Auclair. 1977-2014. #weloveyoujp

It was refreshing to see a super brilliant skier continuously reinvent himself in a sport where most athletes come and go in four-year cycles. JP kept going as his peers dropped into obscurity. He was one of those people who did everything really, really well. Usually, one would harbor at least a touch of brotherly resentment for someone who was just so perfect, his looks mirroring his ageless skiing. Instead you loved him because he was so humble, because he was so nice, and he made you belly laugh every time you saw him. When it’s said that no one ever said a bad thing about JP, that’s not just cliché in his passing, it’s truth.

As a ski designer, he helped develop the first ever halfpipe-specific ski. He helped design the first commercially available 5 dimension ski with rocker and camber. JP and Julien Regnier made skiing powder simple for the masses when they created the forever-copied JJ. He built a burly mountaineering ski called the Declivity. He helped design cutting edge skis, outerwear, gloves and goggles for numerous companies for the past 15 years.

JP directed and edited the most unique and most watched ski movie segment in history, his street skiing segment in All I Can with the Sherpas.

When the entire industry was primarily focused on the race scene and building carving skis, he helped start the first rider-owned, rider-driven brand that was a catalyst to propel what we know as skiing into its current state which many people refer to as freeskiing. JP wasn’t a fan of that verbiage, he thought it was all skiing. ‘They don’t call it ‘freesnowboarding.'”

JP was one of those guys who, when he wanted to do something, he would just teach himself to do it. He wanted take pictures, so he bought my old camera and started taking photos and got really good. He wanted to edit movies, so he learned online (and from Johnny Descesare) how to use Final Cut Pro and eventually went on to direct a major ski film. He wanted to be a better ski mountaineer ,so he learned how to be a guide, how to rock climb and teamed up with Andreas Fransson.

JP loved pizza and there was only one way to get it– diavola style. He was a connoisseur and he would text me pics of his pizzas from Italy, Montreal, Haines, wherever he was, as he knew I shared the love of ‘za. For him, the best pizza in the world was ironically not in Italy; it was Pizza Riva on Tal Street in Munich. It is pretty damn good. We shared meals there when we were in town for the ISPO trade show and laughed our asses off at things you could found funny if you worked in the ski industry for your entire adult life.

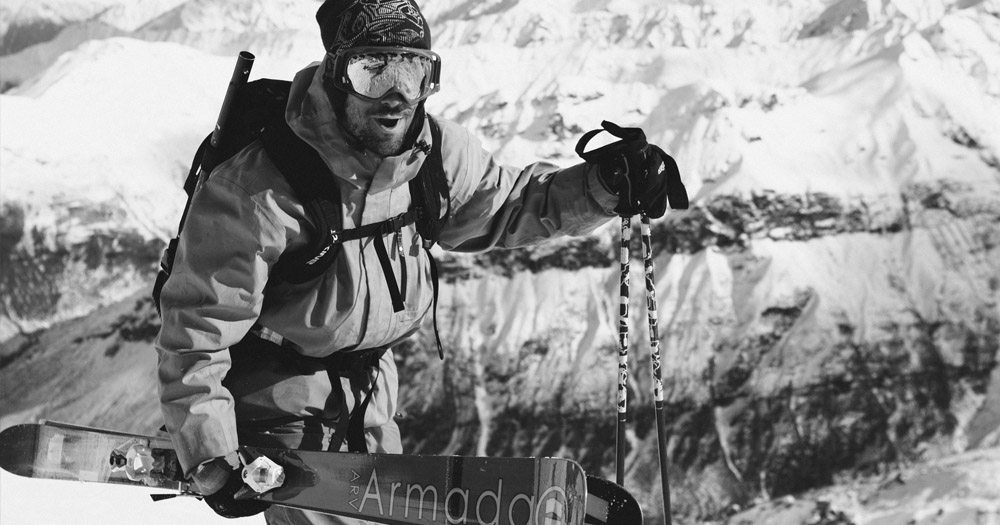

It was over a diavola pie at Pizza Riva that he told me how lucky he was to be able to learn from Andreas Fransson who had become a new partner to JP. He had so much respect for him. JP developed the skill set to be able to ascend and descend with the world’s best in just a few years. Many didn’t know how good JP had become at ski mountaineering. It takes time to be known in that arena and braggers are shot down quickly by the core. After a month-long stint in Chamonix, JP commented, “It’s all calculated and you just ski one turn at a time. It’s a different kind of skiing, but it’s really fulfilling.” That kind of skiing is the pinnacle and only for a few.

JP wanted to become a better ski mountaineer – so he became a guide and learned to rock climb. Who would have thought that a mogul kid from Quebec could have such an impact on the sport of skiing in so many different facets? JP was the only true renaissance man of skiing. There wasn’t another athlete that was able to ski at such a high level in so many different disciplines; nor will there ever now that every single genre is so specialized. Hell, nowadays there is barely a pipe competitor that can ski park on an elite level. From X Games to Ski Mountaineering and everything in between, JP created and defined skiing as we know it. He was the first and the last of two decades of skiers, never to be emulated. Not even close.

To top it off, he worked more behind the scenes than most pros work on snow their entire careers. JP did it all. Whether it was in front or behind the camera, on a computer, in an editing bay, skiing a sketchy pipe or climbing an icy couloir, he did it with the skill and precision. Skiing as we know it doesn’t exist without the contributions of JP Auclair. His natural ability to do just about anything on skis, coupled with his understanding of the business granted him one of the longest athlete careers in the sport.

There is no peace in the loss of JP, but there is solace in the circle of life. JP and I both recently had babies—sons. In the infancy of these lives, it’s harder to become jaded and easier to marvel at what’s ahead. If what they do here is even a bit as creative and brave as what JP has done, it will be exciting. Maybe they’ll build bridges and bring people clean water. Or maybe they’ll just go skiing and make pictures.

–words by Chris O’Connell, Armada co-founder